Memory, fantasy and the healing power of art. Paintings and stories by Rosa Agostinelli from Pacentro

Museo Italiano, Co.As.It, 199 Faraday St Carlton

to be launched on Monday 11 April at 6.30pm by

Dr Moya McFadzean

Senior Curator, Migration & Cultural Diversity, Museum Victoria

rsvp: [email protected]; 9349 9021

With Rosa Agostinelli’s exhibition the Museo Italiano is navigating new, exciting territory. Initially we were anxious; in the end, it was easier than we had anticipated, since it became clear that the challenge for the Museo was, in a sense, to disappear.

The Museo offered its exhibition space, the work of its staff, logistic support, promotion and catering on the evening of the launch. We also found in Dr Moya McFadzean, Senior Curator, Migration & Cultural Diversity, Museum Victoria, a highly experienced and well esteemed professional who embraced with enthusiasm our proposal to launch the exhibition.

The Museo found in Wendy Chan, initially an intern from RMIT University, a curator – herself a migrant several times – brimming with passion and with an aesthetic sensitivity well honed over years of travel and artistic practice. Crucially, Wendy was respectful and spontaneously interested in Rosa’s story and art. The two women, very different in terms of age and cultural background, hit it off well from the beginning.

Wendy saw that Rosa’s story was already there, told in vibrant colours boldly applied on large canvases. Each painting was accompanied by stories, meticulously written in Italian in an old-fashioned school hand. The style of the stories, like that of the paintings, is vivacious, animated and free. It is a spoken style, full of direct dialogue, punctuated with questions to the reader and onlooker, who is always engaged and actively drawn into Rosa’s world with simple hospitality.

In Wendy’s hands Rosa’s story, told in Rosa’s own voice – nothing more and nothing less – was grafted onto the physical space of the Museo Italiano. The Museo has all but disappeared, in that it serves as a mere container, a conduit through which this exuberant visual, textual and emotional tour de force may be shared with the Italian and wider community. We say this with pride because in so far as it has been able to disappear, the Museo has been successful in honouring its democratic cultural mandate.

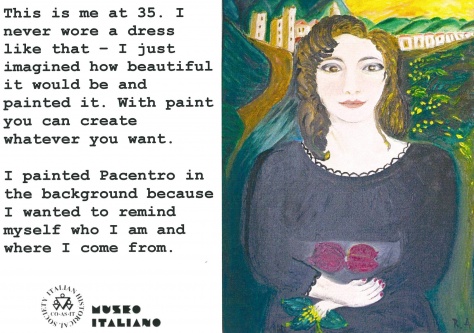

Powerfully sensual in the depiction of the beautiful dresses that Rosa could not afford in her youth but can create now with painting (“with painting you can create whatever you want”), and in the rendering of her womanly curves in the self-portraits as a young person, Rosa’s art reflects a cosmic sensuality, an exuberant fertility of memory and imagination, an opulence, though never a saturation, of sensory stimulation. Rosa has worked all her life as a dressmaker, and her chromatic sensitivity reflects an almost childlike delight in colours and a lifelong practice in combining them.

The same sweeping curves that can be seen in Rosa’s sensual but never vulgar nudes and in her rustic siren (not included in this exhibition) can be seen in the imaginary landscapes of Pacentro (Rosa’s native town which she left at 17), in the angels that populate her fervid religious imagination and in the playful contadina, the farmer girl bending over to pick flowers, so that her large, bell shaped behind occupies centre stage of the canvas. Rosa is quick to add with a wink that she has painted the petticoat, well visible under the contadina’s billowing purple skirt, in black “so that no-one can see her legs”. Humour too is never far from Rosa’s art, which manages to be both playful and dead serious without being incongruous – a bit like life itself.

Open ended reflections on beauty – “certainly that too a gift from God” and one that “lasts into eternity” – and on the heart aches and anguish often associated with sexual attraction and love engage the reader with a series of direct questions that accompany the playful, nostalgic paintings that recreate the magic of first love at a time when men would still serenade their beloved under their windows and furtive letters were exchanged away from the controlling glance of stern parents.

Family life in the rugged mountain village of Pacentro from the mid 1930s through the turbulent war years to 1954, when Rosa’s life changed abruptly forever with migration to Australia, is glimpsed in a series of paintings that recreate street scenes and simple interiors – kitchens with large open hearths, with the fire always on and wine always on the table (“we were poor but our house was full of love”), under the gaze of the blue clad Madonna looking down from the wall . But there is also a cellar inhabited by wine barrels and presses, as well as by an oversize, fat spider through whose heavy web Jesus peers with a large, candid smile. It turns out that the cellar is actually in Thornbury, it belongs to Rosa’s acquaintance Umbertino who is depicted praying (on Rosa’s recommendation). Umbertino’s Pacentran-Thornbury cellar was flooded, and Jesus helped drain the surplus water.

In another painting, Rosa’s parents’ kitchen hosts two characters, husband and wife, from a fairy tale Rosa’s mother used to tell her. Rosa never forgot the tale and the imaginary couple in its fancy clothes looks very much at home in the kitchen. The world as it is remembered (sometimes labelled in the paintings “Pacentro, province of L’Aquila, 1945”) is lovingly rendered in a realistic idiom that makes it instantly familiar to people who grew up in similar small towns in southern and central Italy. On the other hand, this simple world is also, in a natural and immediate sense, an ever enchanted world where you may bump into characters from fairy tales or, more often, into Jesus, with whom one relates informally and directly. Rosa’s texts, as her conversation and her life, are punctuated by an ongoing two-way dialogue with Jesus, who is in Rosa’s world a pervasive force of love and life, but also someone – at times a friend, at other times a figure of authority – with whom one has a personal relationship. In the text that accompanies this painting, Rosa concludes with a reflection, again an open ended one, on the world we live in today: “In the old days people had nothing and were happy. Today we have so much and nobody is happy.” Why is this the case?

Comparisons with today occur also elsewhere, as is natural for people who have been propelled from an archaic world of simple certainties to the complexities and moral quandaries of modernity and lastly to the confusion of the post-modern world. In particular, Rosa is struck by changes in the modalities and rites of love and courtship (“where have all the romantic men gone?”, she asks as she searches for the love songs of her youth on her iPad) and in the relationship between parents and children. This last topic is crucial to understanding Rosa’s traumatic migration story, which is told in some detail in a couple of longer texts.

At one point Rosa states that she no longer believes in love. It is a creation of man, an illusion. “Addio amore!,” she concludes. But then there is a painting expressly created to tell the little known story of the many couples whose love was tragically ended by migration, as the parents would send the girls off to Australia to marry richer men they didin’t know or hadn’t seen for years. “I ask you, is this love?”

Rosa’s life in Australia is also documented. Her home, her suburb – for instance in the small, delicate painting My improvement on High Street, Northcote, which she submitted to Council, hoping that the area could be improved “for women with prams and children”. Rosa recounts in a matter of fact way her family life, her love for her husband and their quarrels, and also “the most beautiful thing in my life,” her children Mauro and Pina and their families (there are many portraits of her children and grandchildren, bright icons painted in joyful colours, not included in the exhibition). Rosa also tells us about “the worse thing in my life”, her beloved son’s premature death two years ago.

After that event, Rosa bravely painted a picture of herself with her son as a child. “I felt a strength and energy coming up from the sole of my feet and filling my heart, and I kept on crying, ‘Jesus, Jesus! Mauro! Jesus!’ and at the end, after three days, my heart, that was like una rosa sfogliata (a rose whose petals had fallen), was back in order. I tell you that my painting has healed my broken heart. There is nothing more beautiful than this. I encourage everyone who has a problem or an issue to paint.”